Another family farm falls © Anthony Fieldman 2022

The world is utterly broken, in two separate ways.

First, the natural systems we inherited—how we interact with the planet—are broken insofar as those that benignly supported us since the outset of homo sapiens sapiens decreasingly do, as we continue to wage war on them in the name of economics. And second, the human systems we invented—how we interact with one another—are broken insofar as they are increasingly destructive, and no longer support our thriving.

Even though our home planet will invariably find new equilibrium (it has survived five mass extinctions, oxidation and five ice ages, so far), our actions are problematic to human thriving in two key ways.

Tubbs Fire: the most devastating in California’s History © Anthony Fieldman 2017

Our Broken Planet

First, the planet on whose predictable and relatively benign systems we have relied for 300,000 years has been grossly disfigured by human activity, and becomes less hospitable every day. The planet now regularly experiences “worst-ever” natural events such as wildfires, floods, earthquakes, hurricanes, droughts, mudslides, atmospheric rivers and extreme heat events, to say nothing of the eviscerated glaciers, plastics-laden rivers, contaminated water supplies, destroyed habitats, acidified oceans, carbon dioxide-choked skies and depleted aquifers that we have created.

By and large, the climate no longer supports either the ways or the places we live today and as such, there will be a seismic upheaval among human societies in the decades to come. Gaia Vince’s Nomad Century is an alarming report precisely because nearly all scientists now agree that our actions will precipitate the forced migration of between one and three billion people fleeing increasingly inhospitable climates for the shrinking Edens that will still support our thriving—in Northern Canada, Russia and Scandinavia, to be precise.

Drought-prone Daasanach family outside their home in the Omo Valley © Anthony Fieldman 2018

Nature always finds harmony among the elements, and it does so in the most efficient way possible, unburdened by human concepts such as ethics, morality, wealth accumulation, sovereignty, in- and out-groups, belief systems or hierarchical judgments related to survival itself (aka who deserves to live), all of which drive modern human behavior.

The planet we share has been endowed with the most remarkable ability to recover from relentless change for billions of years — a period so long that it is without practical reference for human understanding. And it has done so again and again and again and again, since its fiery birth.

And so, as Sebastião Salgado concluded, following his eight-year odyssey — called GENESIS — around the globe, “The Earth will be just fine. It is only us we are killing.”

But. While I welcome you to read my take on how to rebalance the physical planet here, that’s not the focus of today’s thoughts. This piece is about what we can do to improve the human systems that not only led to the disfiguration of the physical world, but also to the degradation of ways in which we interact with one another, because it is those broken systems that have driven us to the brink.

A statement made by E.O. Wilson always comes to mind when I turn my thoughts to this subject:

“The real problem of humanity is the following: We have Paleolithic emotions, medieval institutions and godlike technology. And it is terrifically dangerous, and it is now approaching a point of crisis overall.”

The reason that the 20th century was more destructive than all those that preceded it, and why the 21st is just getting started and may yet be our end run, is the fact that the tools we now employ to fuel those “medieval institutions” are now indeed “god-like” and, realized in full, could destroy us.

As such, our top priotity should be the replacement of our broken systems.

Black Lives Matter march © Anthony Fieldman 2020

Our Broken Systems

The inescapable fact is that the systems humans we created to support our collective thriving as a species are all utterly broken.

That’s the good news.

Why?

For context, humankind is given to great bouts of inertia, aka “resistance to change”, even if the benefits of doing so are clear. Our pattern is always the same. Innovators ideate, then proselytize. Early converts join. Dogmas are invented, then take hold. Institutions codify them. The masses join in. Habits form. Challenges to now-established dogmas are met with hostility.

Repeat.

Most of us don’t like change, or at least what we consider unnecessary change. Change is difficult because it requires a serious investment of thought, time and action. Change is also scary to those who don’t understand it, or focus on the short-term impacts on their lives today, instead of the greater good it may bring tomorrow. For some, there’s good reason. It’s hard to be generous when you’re starving. But for most, it’s the lack of insight, understanding, resources, energy, will and/or trust that typically gets in the way of the new.

Until there’s no choice.

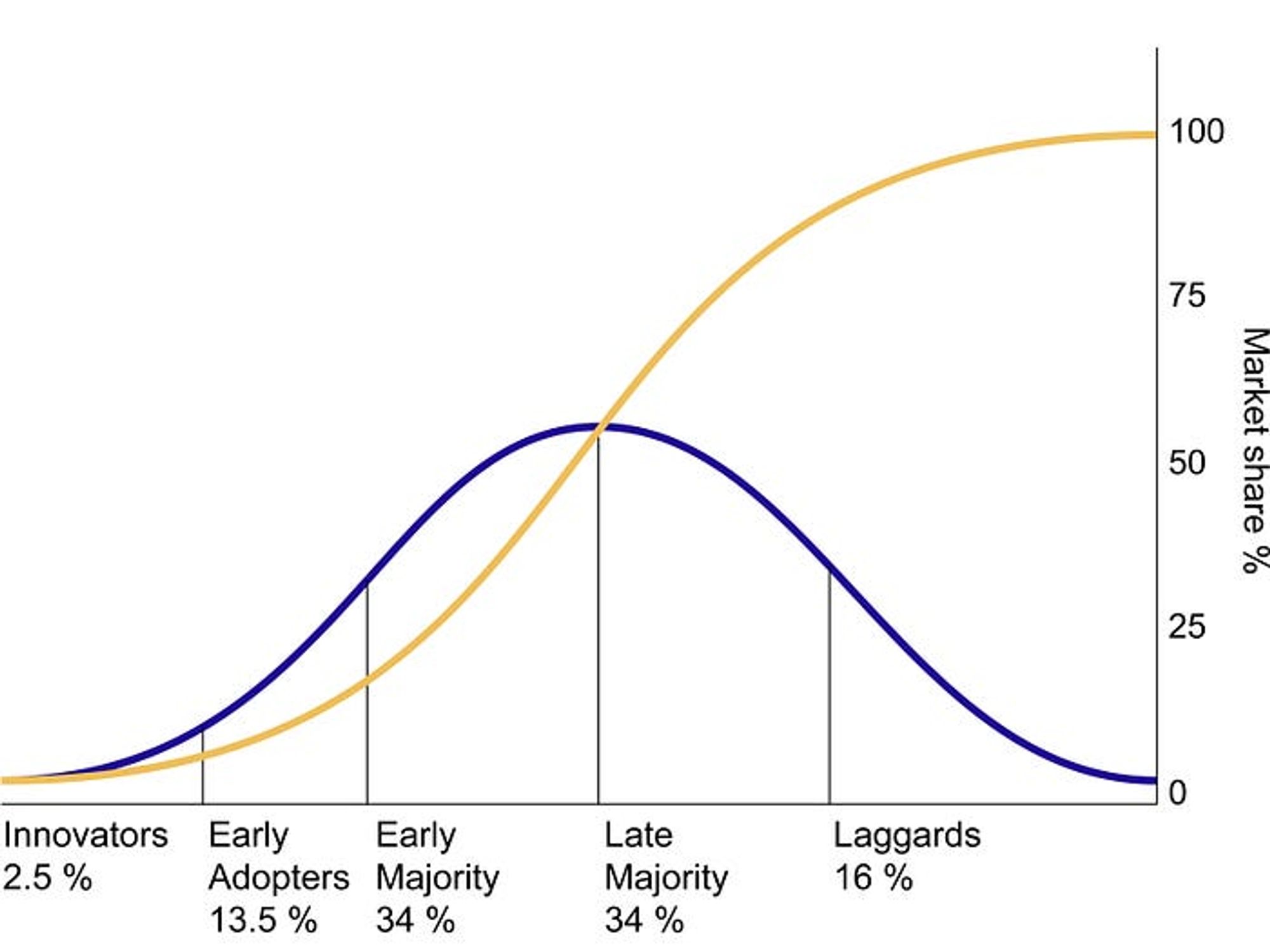

Everett Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations Theory is an elegant device that uses the brilliant bell curve to explain the long trajectory of change. While Rogers applied it to commercial markets, it frankly applies to every sphere of human activity.

By Rogers Everett — Based on Rogers, E. (1962) Diffusion of innovations. Free Press, London, NY, USA., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18525407

I wrote about a piece about the costs of The Human Bell Cuve here.

Changing major systems that impact most of us is hugely difficult because of its usual high cost to our short-term comfort and gain, and because it forces us back to the drawing board for things that took ages and countless resources to create in the first place. Most of us don’t have the stomach for that kind of upheaval; and if we’re honest, most of us don’t know how to approach the ideation and implementation of something that might be better than what exists, even if we were to somehow agree that the current paradigm was worth replacing.

We rarely agree.

There’s also the fact that anything unknown ignites our oldest and most powerful emotion.

As H.P. Lovecraft said:

“The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.”

Or, as the ancient Latin proverb goes:

“Better the devil you know than the devil you don’t.”

And so, how is the fact that everything is broken good news?

It is good news precisely because when things are broken enough, we are forced out of our passivity, and at that point there is a small window of opportunity for us to improve upon things before we settle back down again into business as usual.

The pandemic has thus created a once-in-our-lifetime opportunity. Not only did it force us up out of our chairs for fear of dying (see: Lovecraft), it also showed us what was broken, and even how.

Leonard Cohen put it magically in his song Anthem:

“Ring the bells that still can ringForget your perfect offeringThere is a crack, a crack in everythingThat’s how the light gets in”

It is time to let the light in.

The structural issue here is that our rigid conceptual and institutional systems — and our inertia itself—stand at odds with the reality that natural systems continually change. And instead of embracing a flux mindset (to borrow April Rinne’s term for “unsticking your mind from the constructs and assumptions that you hold unconsciously”), we use most of our faculties to prevent change from happening, at all costs. And we do so with the physical world as much as we do with our own psychological mindsets.

For example, we do things like purchase, hold and develop fixed land assets, then either exclude others’ enjoyment of them or charge them for the privilege. The Lenape didn’t understand our concept of land ownership when the Dutch traded them wampum for New York City.

“The Lenape believed they were receiving gifts to share their land with new neighbors. As stewards of the land, they didn’t believe it was theirs to sell.”

The first thing we did, of course, was build a wall to keep them out, and called it Wall Street.

Fort Amsterdam’s Wall Street (at right), c. 1660

Our Finite Games

The problem with fixed land ownership is twofold. First, it prevents us from dynamically responding to climate events, as we used to. Entire cities, home to nearly a half a billion people, are nearly guaranteed to be subject to forced abandonment as sea levels rise and coastal storms increase.

Today, the share economy shows the path toward two phenomena: the dynamic use of land for housing that services like AirBnB, Nomad Stays, Outside, Anyplace, Flatio, Selina, Boundless Life, Remote Year, Nomad Pass and conventional time shares already encourages; and the direct reduction to retail costs that pooling resources and sharing in the savings naturally precipitates.

Regardless of where our home is, or for how long, we have put access to shelter out of reach for too many economically through the artificial inflation of prices (more on this below), regulatory barriers, lack of adequate focus on innovation in prefabrication and advanced fabrication—which are inherently deflationary (more on this, too, below), prohibitive financing terms, and the lack of limits on greed-fueled opportunism related to real estate.

We hoard not only land, but also objects, rights and labor for our exclusive control and use, then leverage our power over others to maximize personal gain instead of sharing what we’ve created or secured freely.

And throughout modern human history, once our societies had expanded beyond relational clans, we have willfully competed with one another for everything, rather than chosen instead to collaborate as our species is hard-wired to do.

As brilliantly conceived in James Carse’s Finite and Infinite Games, we have elected to play finitely with one another, competitively, for pieces of a conceptually limited pie.

Resource limits are an inherently flawed concept and the outcome of this thinking is, as everyone knows and accepts, the creation of winners and losers. This is not only toxic, it is unnecessary. While it may be benign enough in games without real consequences—like sports—it is decidedly less benign when what’s on the line is our physical or mental health. That is, when we compete for access to food, clothing, shelter, education, clean water, medicine and jobs—or struggle to find love, acceptance, friendship, support, community and connection—everybody loses.

The notion that there are limits to supplying what we each need to live vibrant life is totally false. In fact, everything I listed above, providing for our core physiological and emotional needs, are not only abundant, they are limitless. We simply choose not to share resources and ideas with one another freely because the economic paradigm we’ve designed makes this impossible.

The chief exception to our interpersonal game-playing is how those with a healthy family dynamic treat children or parents. Conversely, you could easily argue that families with the most money are often the most willing to cause great harm to one another through competitive manipulation for access to a gluttonous pie.

Temptations are simply too great not to, in an economically incentivized society.

Which is the core issue.

I’ve written many pieces that touch on different aspects of the myth of scarcity, if you care to go down the rabbit hole on issues like overpopulation, redistribution, public welfare, tribalism, risk-taking, nationhood, inflation/deflation, education, scarcity itself, relationships and/or food.

Unsurprisingly, what drive nearly all finite games we play are two things: the economic model we’ve invented as described, powered by the myth of scarcity; and the false notion of human exceptionalism—that all humans are better than non-human creatures, and that some humans are better than other humans. These conceits contravene everything else found in nature.

Finite games have led to a world divided by competition between factions, rather than united by the fact that there is only one world, and everything on it shares a single fate.

The economic model of late-stage capitalism has pitched every human against one another in a bid to extract the maximum as cheaply as possible, in lieu of investing in resource amplification and sharing. To say it again, there is enough for everyone. We only elect to artificially compete for pieces of it and extract it unsustainably, rather than take the natural steps to pool our resources to create and share in true abundance, then use it sustainably.

The end result of these things is a human population whose daily lives are a struggle against the natural world and other humans, rather than an eight billion-strong army of collaborators in managing the endless bounty of planet Earth.

Fighting for acceptance © Anthony Fieldman 2020

So What’s Broken, Exactly?

The result of our strategies is a broken human world underpinned by our religious adherence to the human fiction of money and economics.

This manifests in myriad ways.

The climate is broken (insofar as how hospitable it is for us) because we have relentlessly focused on short-term economic gain (via resource extraction and use) rather than long-term sustainability. Housing is broken, because we’ve made the fundamental need for shelter the single most unattainable (i.e.: expensive) asset in human societies. Food is broken, because we’ve decided that bolstering quarterly returns was worth turning food into the biggest killer on Earth, while simultaneously destroying 38% of our global landmass to achieve it. Education is broken, because we’ve declassed and honed people into specialized mechanisms for profit generation, robbing us of our inherent capacity for creative polymathy. Work, too, is broken for much the same reason, as graduates become cogs in a globally splintered workforce of specialists without a unifying framework for human thriving. Public safety is broken insofar as we weaponize our superficial differences (encoded in fictions like nationhood, race, socio-economics and religion) rather than unite under the true banner of our common humanity. And Politics is broken because it is led by a legion of lawmakers whose modus operandi is encoding rigid governing structures based on fixed ideologies that protect their personal interests, rather than the hard work of continually engaging, listening, synthesizing and then championing the will of the people they have sworn to protect (or at least should). See: bribery, lobbying, extortion, cronyism, nepotism, parochialism, patronage, influence peddling, graft, and embezzlement. Moreover, politicians adhere to the fiction of nationhood, waging life-ending war on those outside our militarized boundaries, just as we did to the Lenape.

But.

There’s good news, too, in two forms.

First, as I mentioned earlier, the natural world remains unbroken. It’s simply different from the one we inherited. We will adapt as we always do to its increasingly inhospitable climate. If our forebears could do it during the stone age on a frozen planet with nothing but spears and animal skins, we can, too.

Second, given that human systems are nothing more than fictions most of which are mere decades or centuries old, we can and should replace outdated competition-based systems with collaborative ones that take advantage of the physical and conceptual resources at our disposal.

Which is where our collective energies need to go. If we are to adapt to a planet we disfigured we must advance the failed systems that brought us here, focusing on an approach that maximizes our collective, long-term thriving.

Tribe © Anthony Fieldman 2018

A New World

Back in October, I dared to share the world I dream about.

Everything I wrote, both there and in other pieces, is easily achievable, because the means of doing so already exist.

These include ending hunger, housing and educating everyone, sharing resources freely with anyone in need while powering everything for free—applying the seventh-generation principle to our actions, prioritizing the common good over the gains of the individual, allowing deflation to naturally lower the cost of everything until it approaches zero, foregoing labels that distinguish us artificially (nature doesn’t do cults), and yes, repairing the damage we’ve inflicted on the Earth.

Healthy Minds, Healthy Acts

To do this, we’d have to retool our relationship with destructive behavior.

We’d have to start with the most difficult of all tasks: healing those whose traumas, fears and insecurities that have led to the emotionally and physically destructive behaviors that have broken everything.

Religious zeal, colonization, aggression, policing, bullying, patriotism, competition, racism, greed, indictment, sexism, exclusion, expulsion, prosecution, persecution, hate speech, law enforcement, consumerism, and possessiveness are all symptoms of emotional sickness, and must be treated as such.

Finite Values © Nikki Harre

Psychotherapy, mentorship, education and inter-generational wisdom—the tools required to heal people—are all resources that are free, and thus should be shared as such, rather than sold to people who can afford the privilege.

If we focused on enhancing people’s emotional health, intellectual capacity and creative output, we would—to say it again—create an eight billion-strong army of collaborators in managing the endless bounty of planet Earth.

All Before One

The cost to produce energy and goods could be borne by a planetary array of humans, machines and AI working together to optimize generation, distribution and repair, which would allow us to then distribute it all, freely.

It wouldn’t take us more than a few years of working together to devise a plan for truly free energy generation and distribution, perpetually. Tesla invented as much 100 years ago, before George Westinghouse killed the project because he couldn’t monetize it.

Tesla was eventually undone by what he called “ignorant, unimaginative people, consumed by self-interest” — powerful men that sought to protect the immensely profitable, low-tech industries they had spent a lifetime building.

Proof point: Tesla actually co-invented the radio with Guglielmo Marconi (who gets all the credit) and led the world to more than a century of free, global transfer of communications and ideas.

Money—the root of all evil—doesn’t actually need to be replaced. It simply needs to evolve. The fact that the world’s richest billionaires could end extreme poverty seven times over is just the beginning. The combined productive output of powerful machines, a planetary digital network, artificial intelligence and human ingenuity (for invention and optimization) can not only provide for the needs of all humans today, the cost for doing so is quickly approaching zero. That is, it is all inherently deflationary, as eloquently presented in the book The Price of Tomorrow.

The author Jeff Booth points out that the concept of inflation and growth—two metrics that galvanize nation-scaled activity, globally—is not only ill-conceived, it is unnatural, insofar as it contravenes the fact that everything is becoming inherently less expensive with time. Thus we are now in an entrenched paradigm of creating artificial growth through the creation of very real and crippling debt. It now costs $3 of debt to create $1 of GDP growth, globally.

We may have to reconcile these things soon, regardless of how we feel about money, given that the natural outcome of these systems is an increasingly unemployed and unemployable human species.

The Rise of the Useless Class

As I wrote for Codex, we are on the doorstep of hosting a global population of unemployable people.

This is great news.

Pew Research writes, of a gathering of 979 technology pioneers, innovators, developers, business and policy leaders, researchers and activists:

“The experts predicted networked artificial intelligence will amplify human effectiveness but also threaten human autonomy, agency and capabilities. They spoke of the wide-ranging possibilities; that computers might match or even exceed human intelligence and capabilities on tasks such as complex decision-making, reasoning and learning, sophisticated analytics and pattern recognition, visual acuity, speech recognition and language translation. They said “smart” systems in communities, in vehicles, in buildings and utilities, on farms and in business processes will save time, money and lives and offer opportunities for individuals to enjoy a more-customized future.”

An unemployed population supported by a non-human workforce that needn’t eat, sleep, take time off, be trained, receive payment or be emotionally mollycoddled is the exact mechanism that could finally render the conversation about “working to live” moot.

The cost of life is approaching zero. Economic systems are preventing the savings from reaching all of us.

The release from artificial growth mechanisms will unlock untold potential for humans who finally have the time to do what they love, instead of what they think is marketable. Booth writes:

“We are trapped in a system where we don’t know what we would do with ourselves if we didn’t have jobs … allowing abundance without the jobs might actually open an entirely new enlightenment era where we have time to enjoy the benefits that technology brings.”

Forbes Magazine, that bastion of finance, industry, investing, and marketing ideas, wrote the following, about the topic of (true) deflation:

Humans will probably always work, in the sense that we will always have projects and goals. But what a sad species we would be if we always needed that work to be in the form of jobs, directed by other people, with a need to generate revenue. There are three types of people who prove that you don’t need a job to have meaning: aristocrats, comfortably-off retired people, and children.

Think about it. What wouldn’t we all give to live like an aristocrat, to retire from the grind, and/or to play like children do?

It’s not only possible, it’s the answer.

Once we stop fighting one another for scraps to live in the abundance created by deflationary technologies and a planet-wide system of distribution, shared freely, the finite games of war, competition, greed, social climbing, extraction and patriotism will be defanged. As a result, poverty, sickness, deprivation, homelessness, hunger, and many forms of human stress will disappear automatically, because unlimited access to human, capital, technological and physical resources will become free.

As will we.

Final Thoughts

The climate is broken, but can be fixed once we stop focusing on short-term economic gain. We have the tools to repair it today.

Housing is broken, but can be fixed once we create homes for everyone, affordably in the short term, and free thereafter.

Food is broken, but can be fixed once money is removed from subsidizing (through debt) unhealthy foods their production, at which point human health and access can re-emerge as cardinal outcomes.

Healthcare is broken, but can be fixed once money is removed as an access key. Illness prevention saves money, but starves capitalism of its fuel. Illness treatment costs money, feeding capitalism while depriving human vitality.

Education is broken, but can be neutralized with a digital network of free classes and workshops in the near term that already exist; and by removing the need for human-generated economic output in the mid-term, once technology fully takes over.

Work, too, is broken, but can be fixed once we no longer “work to live”, at which point we can stop treating one another transactionally as means to an end. It’s coming, which means Universal Basic Income is also coming, hopefully before the house of cards of artificial debt comes crashing down on our ears.

Public safety is broken, but can be fixed in two ways. First, crimes caused directly or indirectly by economic straits will plummet once money no longer drives our desperate acts. And second, once we accept the fact that we are all in one boat and will sink or swim in a form of shared fate, our tendency toward bigotry should also diminish.

And finally, politics is broken because it is largely exploitative, and once income evolves into a global resource borne on the backs of the powerful machines, a planetary digital network, artificial intelligence and human ingenuity that are already in our hands, then bribery, lobbying, extortion, cronyism, nepotism, parochialism, patronage, influence peddling, graft, and embezzlement, too, will lose their luster.

At that point, things will no longer be broken. Once we’ve fixed them all—and we can, today—we can finally turn our free attention to the very thing people excel in, beyond anything we’ve ever created: understanding and administering to other humans, for our very human qualities.

It’s time to let the light in.